- Home

- Jonathan Alter

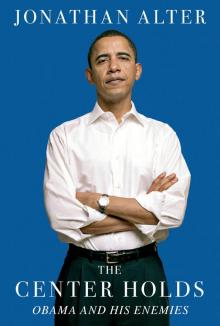

The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies Page 3

The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies Read online

Page 3

It was time for some personnel changes. The two biggest presences in the White House in the first two years, Rahm Emanuel and Larry Summers, director of the National Economic Council, had (along with Secretary of the Treasury Tim Geithner) helped Obama put out fires that could have consumed the U.S. economy. While this was taken for granted by Wall Street and much of the public, an appreciative president had not forgotten. But Emanuel was tired of being undermined by Valerie Jarrett, and he was anxious to run for mayor of Chicago. Summers, for all of his brilliance and value as what one senior aide called Obama’s “security blanket,” had proven high-handed in his interactions with other administration officials, which impeded nimble policymaking. In 2009 and 2010 Summers slow-walked small business initiatives that were relevant both to recovery and to the president’s political fortunes, and he blocked requests from Governor Ed Rendell of Pennsylvania and Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood to include more money for high-speed rail and other infrastructure in the Recovery Act. He felt it wouldn’t jolt the economy quickly enough because so few projects were “shovel-ready.” So in 2009 only $87 billion out of the $787 billion stimulus had gone for water and transportation infrastructure. This became one of the president’s major regrets.

With the message failures of 2010 fresh in his mind, the president decided to change the public face of his administration. He wanted fresh blood, but there was a cosmetic dimension too: The first lady and Jarrett, the Obamas’ closest confidante, weren’t thrilled with the way David Axelrod came across on TV. Axelrod had vaguely planned to leave in the spring of 2011; now the president moved up his departure date to February. He told an exhausted Axelrod that he wanted him to go back to Chicago to rest and gear up for the 2012 campaign.

Press secretary Robert Gibbs hoped to become Axelrod’s replacement as senior adviser, though he knew the job had long since been reserved for David Plouffe, the 2008 Obama campaign manager who had stayed out of the White House for the first two years. It didn’t help that Gibbs had also run afoul of Jarrett, cursing her out in a meeting for misrepresenting the first lady’s views on a minor matter. Once he indicated that he didn’t want to stay through 2012, there was no job for him except possibly head of the Democratic National Committee, which he wasn’t interested in. Obama, knowing that Gibbs wouldn’t accept a job without portfolio, offered him one, a sign that the president was a little more manipulative than he appeared. The press secretary left shortly thereafter to write and give speeches, and he later became an especially effective Obama surrogate in 2012.

Everyone else, even Jarrett, got the once-over in the president’s mind. She was just a hair below Chicago buddies Marty Nesbitt to the outside world.JU and Eric Whitaker as best friend of Barack, but she was not immune. We have to put personal feelings aside as we retool, he told Rouse. “I’d look at myself too if I wasn’t president, but I can’t remove myself.” This was part of Obama’s way of breaking the news to Rouse that he wouldn’t be promoted from interim to permanent chief of staff, a decision that caused disappointment within the White House, where Rouse was seen as the unprepossessing and kindly uncle who looked out for younger staffers. Rouse and Jarrett would stay as senior counselors, but the president’s new top team inside the White House would also consist of Plouffe, his 2008 campaign manager, and Bill Daley, hired as the new White House chief of staff on the strong recommendation of fellow Chicagoans Emanuel and Axelrod, who thought Daley would help the president get reelected.

Plouffe found working in the White House as stifling as “life on a submarine.” But the man Obama most credited with his historic 2008 victory slipped seamlessly into his new role as inscrutable consigliore. “You know when people play cards close to the vest?” Daley said later of Plouffe. “He’s got his cards [facedown] on the table and he doesn’t even look at them. So how are you gonna figure what his cards are?”

Daley took over as chief of staff without having ever been close to Obama, who had a distant relationship with the Daley family going back two decades. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley never forgot that Obama had taken a vacation instead of casting a key vote in Springfield when he was in the Illinois State Senate. He wasn’t amused by the story, repeated in several books, of Obama as a young law school graduate accompanying Michelle to meet Jarrett for the first time for the purpose of deciding whether Daley’s City Hall was good enough for his junior lawyer girlfriend.

Bill Daley, the mayor’s younger brother and a former commerce secretary under Bill Clinton, took a risk in late 2006 by becoming the first major Democrat to endorse Obama over Hillary Clinton. But even that was complicated. While Obama’s campaign was pleased, Axelrod called Bill Daley and begged him to make it clear to the Chicago Tribune that he wouldn’t be in the inner circle. Obama and his team were worried that he would look like a tool of the Machine. In mid-2007, when Obama trailed Clinton by 30 points in the polls, Daley figured Obama’s campaign was a lost cause and said so a little too loudly. He was offered nothing when Obama became president and was rarely consulted in the first two years.

The Daleys also had an uneasy relationship with Jarrett, who had worked in Chicago government in various capacities. The mayor found her indecisive as city planning commissioner and refused to make her his City Hall chief of staff. Bill Daley thought he had a decent relationship with her, but she was unhappy when the president chose him over Rouse as White House chief of staff and worried that it would affect her role as liaison to the business world.

Jarrett always appeared calm and self-possessed in public, but on learning that the president was poised to hire Daley she was in an agitated state. She went to Axelrod’s office, just steps from the president’s private study. She had crossed swords with Axelrod in the 2008 campaign and in the first two years in the White House; she surely knew that Axelrod had pushed strongly for Daley’s hiring. But she sat on his little couch and opened up to him anyway, confessing to her fellow Chicagoan her anxiety about the road ahead.

Obama headed into the third and most dismal year of his to the outside world.JUpresidency with a staff in turmoil and a family that had lost its appetite for living in the White House. “Michelle would be happy if I quit, but I can’t turn this over to Palin,” he said, only half joking.

In the period after the shellacking it often seemed that Obama didn’t like being president all that much. More than one friend said that he’d be a happy guy in 2017, when his second term was over. That was assuming, of course, that there was a second term. Voters, he would learn, have a way of sensing who really wants the job.

* * *

I. Many Republicans attributed their huge losses in 2006 and 2008 to the Iraq War. They argued that without that war there would have been no Democratic majority, no President Obama, and no Obamacare.

II. The word

2

Tea Party Tempest

Significant political change in the United States is usually the result of social movements that work their way into the political realm. The years 2009–12 saw the emergence of an angry reactionary movement that will be best remembered for the part it played in the 2010 midterms and for the severe political dysfunction that flowed from that election. Its racial and ethnic undertones were subordinated to a brilliant marketing pitch: the old whines of even older white conservatives bottled as a refreshing new tonic for anxious voters.

At bottom, the Tea Party—the fastest growing political brand of the modern era—was more a temperament than a specific agenda for change. Its unifying idea was visceral opposition to the left in general and to Barack Obama in particular, especially to Obamacare and what conservatives considered the “socialistic” expansion of government. The movement was animated by a sense of foreboding that the survival of the nation was on the line, with opposition to immigration and Islam bringing together disparate elements of the coalition. Obama’s “otherness,” his not-from-here quality, became a euphemism for race and fueled absurd conspiracy theories.

At first it seemed as if t

he Tea Party was a godsend to the GOP. The energy it brought to the conservative movement helped its five preexisting wings get along. The economic establishment wing (deficit hawks), the neoconservative wing (foreign policy hawks), the antigovernment libertarian wing, and the Christian right wing all “over and over.”leContract with America worked together with the help of the Murdoch-owned media wing: Fox News, the Wall Street Journal editorial page, and the New York Post.

One of the achievements of the Tea Party was to convince social conservatives to embrace an economic agenda. To Rob Stein, one of the founders of the liberal Democracy Alliance, this was an important moment in recent political history. Stein figured the billionaires subsidizing the conservative infrastructure must have experienced “orgiastic joy” when they found out the Tea Party could be the arms and legs of libertarianism and turn it into a grassroots movement. The result was that one strain of conservatism, an ideology of enlightened selfishness, took center stage.

It wasn’t clear if the energy behind the movement would translate into genuine power on the ground, where the Republican gap with Democrats seemed to be shrinking. Unions, once the backbone of the Democratic Party, had slid from representing 35 percent of American workers in 1954 to 11 percent in 2012 (and only 7 percent in the private sector). Labor still had plenty of bite, especially when it came to the use of union dues for political campaigns. But the left trailed the right in building party infrastructure. It had no comparable network of closely linked organizations and no feeder system for the young. The progressives’ best training ground and alumni association was the 2008 Obama campaign.

THE TEA PARTY was born three weeks after Obama took office, when a libertarian business reporter for CNBC, Rick Santelli, lit into the new administration on the floor of the Chicago Board of Trade for making Americans “pay for [their] neighbor’s mortgage [when he has] an extra bathroom and can’t pay the bills.” In fact Obama had unveiled a modest foreclosure relief bill that week but never endorsed a full housing bailout; he and his advisers thought it would have been political suicide to rescue every homeowner facing foreclosure. But Santelli’s call for a “Chicago tea party” resonated, and within hours twenty conservative activists using the Twitter hash tag #TCOT (Top Conservatives on Twitter) held a conference call to build on the idea. Greta van Susteren’s Fox News Channel show picked up the story, and by tax day on April 15, 2009—less than three months after Obama took office—tea parties had spread to 850 communities, fueled by round-the-clock coverage on Fox, where four anchors went so far as to cobrand with the movement by reporting, and cheerleading, on scene from “FNC Tea Parties.”

It was hard to discern what lay behind the sense of outrage. Amy Kremer, a former flight attendant and real estate broker who helped organize Tea Party Patriots and later Tea Party Express, believed that the million or so people who took part that first spring were “united by anger over Washington not listening.” But listening about what? The bank and auto bailouts were rarely mentioned by Tea Party members asked about their grievances. Despite some grumbling, no one had organized street protests on the right when President Bush pushed through huge bailouts, not to mention trillions in new spending on wars and a prescription drug benefit that wasn’t paid for.

In late 2009 Obama said that he thought it was the debate over the stimulus that led to the Tea Party. (At the time, he was paying so little attention to the protesters that he Scarborough, earlyinadvertently called them “tea-baggers.”) But when he saw the “Take Our Country Back” placards on television, he was under no illusions about the racial subtext. “ ‘Take back the country’?” he said one night to a couple of friends gathered in the Treaty Room in the residence. “Take it back from . . .?” He didn’t need to finish the sentence.

In twenty-first-century America, race was hard to talk about beyond a small circle of intimates. Even the most ardent Tea Party members went to pains, at least on the surface, to point out that they had black friends and acquaintances. While only 8 percent of self-described Tea Party adherents were nonwhite (compared to 11 percent of the GOP), members liked to brag that the movement sent two African Americans to Congress, Allen West of Florida and Tim Scott of South Carolina, and provided most of the money and staff for the presidential campaign of Herman Cain, a black man and former CEO of Godfather’s Pizza.

Joel Benenson, the president’s pollster, was convinced the Tea Party was a bunch of hype. He believed that those who self-identified as Tea Party members were no different from older white, very conservative Republicans. Democrats further comforted themselves that the Tea Party was the product of “Astro-turfing”—fake grassroots planted from Washington.

It was true that a few Tea Party groups received financial backing from FreedomWorks, an outfit run by former House majority leader–turned-lobbyist Dick Armey (and backed by major corporations), and from Americans for Prosperity, funded by the billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch. AFP suggested its true orientation when its Texas branch gave its Blogger of the Year award to one Sibyl West, who called Obama the “cokehead in chief” and said he was suffering from “demonic possession.” By organizing training sessions and providing help with publicity, FreedomWorks and AFP watered the grassroots.

But the movement, made possible by the new social media world, was not a creature of billionaires. The Tea Party was propelled by the same forces that had brought Obama to power: disgust with government and a bad economy. It was best understood as a loosely organized collection of several hundred tiny groups connected mostly by websites and social media. Even Tea Party Patriots, the biggest group, was linked to only about half of the sites claiming to be Tea Party–affiliated. Only about a quarter of the small Tea Party websites even linked to FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity, suggesting that most of the movement was organic as well as Astro-turfed.

The scores of different tea parties had no leader, but Mark Meckler and Jenny Beth Martin of Tea Party Patriots probably came closest. Once a distributor and recruiter with Herbalife, a multilevel marketer of controversial nutritional supplements, Meckler believed in keeping the Tea Party independent of the GOP. Another group, Tea Party Express, disagreed. With the help of Sal Russo, a seasoned conservative political operative who had worked for Senator Orrin Hatch and former housing secretary Jack Kemp, Tea Party Express organized bus tours around the country and PACs that poured money into Republican campaigns in 2010, starting with Scott Brown’s campaign in Massachusetts. Tea Party Express came of age on September 12, 2009, which Russo described as a “holy day for the Tea Party crowd.” Between 600,000 and 1.2 million people rallied at scores of events across the country, underwritten in part by money from the conservative Scaife Foundation, the tobacco giant Philip Morris, and other corporations.

The willful misuse of history was inevitably part of the Tea Party story. Harvard professor Jill Lepore argued that Tea Party activists practiced “anti-history,” a form of retroactive reasoning that allowed them to say with a straight face that “the founders are very distressed over Obamacare.” They also practiced “historical fundamentalism,” in which the Constitution and the Declaration were applied as if they were religious doctrines.

Whatever the Tea Party’s shortcomings, something big and uncontrollable had been loosed upon the political system, at least for a time. In the 2010 midterms, according to preelection surveys and exit polling, self-described supporters of the Tea Party made up 20 percent of the American population and 41 percent of those who voted. The name was so appealing, so redolent of the Founders and American ideals, that more than two-thirds of Republicans wanted to be connected to it in 2010.

AS TEA PARTY activists looked to the Founders, progressives found more to learn from the New Deal. But sometimes they didn’t learn enough. With millions of homes facing foreclosure at the depths of the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt brushed aside objections and pressured Congress to act. He launched the Home Owners Loan Corporation, a government agency that insured private l

ending and bought underwater mortgages from banks in exchange for safe government bonds. The agency sent special government representatives door-to-door to explain its housing programs, evaluate loans on a case-by-case basis, and help strapped homeowners find jobs, rent empty units, and even apply for public assistance.

All told, “the Incredible HOLC,” as Bill Clinton’s favorite economist, Alan Blinder, called it, saved more than a million homes—or 10 percent of nonfarm households—between 1933 and 1936. This would be roughly equivalent to 12 million households today, the approximate number of mortgages still underwater in 2012. A 20 percent national default rate in the 1930s did little to derail the program. By the time the HOLC closed in 1951, its mortgages were all paid off and the houses resold at a tidy profit for the government. By then a whole generation of Americans recalled that it was Franklin Roosevelt who helped them keep their homes and farms.

The same would not be said of Barack Obama, although on health care reform, he did resemble FDR; over the objections of Biden, Emanuel, Axelrod, and most of his other advisers, he pushed forward on reform that even Roosevelt wasn’t capable of achieving. But housing was a different story. By 2012 the housing crisis that began in 2007 showed no signs of easing, as the number of foreclosures hit four million, not including the millions who sold their homes at a loss. In swing states like Nevada, Colorado, Ohio, and New Hampshire, more than a quarter of all homeowners were underwater, meaning their homes were worth less than what they owed on their mortgages; in Florida the figure was more than half.

Through most of 2009 the White House failed to grasp the import of the Tea Party movement, except when it came to housing. Within days of Santelli’s rant on the extra bathroom, Obama’s political advisers decided they didn’t want to get on the wrong side of homeowners who had faithfully paid their mortgages and were in no mood to help those who had not, even if it helped stanch the decline of property values in the neighborhood. rape and incest. vJoel Benenson’s polls found that even underwater homeowners didn’t want to see bailouts of irresponsible borrowers. The Tea Party was the majority party on that one.

The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies

The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies